There are many culinary techniques that have been lost to the common household cook over time. One such technique is deboning a whole chicken. And by that I mean removing the skeleton of the chicken while it is still whole. The benefits of this are 1) you have now turned your chicken carcass into a roast, and 2) once you remove the bones, you can fill in those spaces with dressing.

The LaRousse Gatronomique, in its section on chicken, describes how to debone a whole chicken in five easy steps (cut down the length of the backbone, remove the feet, separate the meat from the carcass, remove the carcass and bone each thigh from the inside, lay the bird out flat and stuff), complete with photos. My counterpart followed their steps, for the most part. And it's really not as difficult as you think if you follow their basic strategy, take your time, and start with very, very sharp knives.

First, cut the tips of the wings off and set aside. We did this right from the start, figuring it would be easier before the bird was all cut open.

Then, as per the Gastronimique, start with the spine. Laying the chicken on your board, breast side down, use your boning knife to cut the skin along the spine.

Continue using your knife to fillet the tissue from the bone, gradually working your way down the rib cage.

When you reach the wing, use your boning knife to pop the joints that connect the wings to the bird. Cut through the joint using either your boning knife or your medium chef's knife and set the wing aside. The shoulder joint should already be popped, so cut through the tissue connected to that upper bone, and pull it out.

Repeat on the other side, and remove the skeleton.

The legs are a little trickier. Starting at the hip joint, cut down the length of the bone, gently easing the bone out until the knee joint is exposed. Pop that joint as well, and remove the thigh bone.

Using your boning knife, cut away the skin around the outside of the bottom of the drumstick, approximately the ankle of the chicken. Then, gently ease that drumstick bone out and set aside.

Take your bones and start a pot of stock. Flatten out your carcass and prepare to stuff.

The stuffing we used was made of the remains of a loaf of home-made bread, cut into cubes; the chicken giblets sauteed and minced; a little splash of the giblet cooking oil; and a dollop of home made mayonnaise Do not underestimate the impact of a little home made mayo. It is, after all, egg yolk and oil, and what in the kitchen does not benefit from those two items?

To stuff the deboned bird, first fill in the cavities left by the wing and leg bones. Then, spread the remaining dressing over the rest of the inside of your chicken and close it up.

The traditional method for closing up a bird prepared in this manner is to sew the outside edges together. You can do this with a metal darning needle and some cotton thread. Be sure to check that your thread is cotton and not some synthetic before you sew it up and get it in the oven. Other wise you will have anxiety at the thought of the man-made, probably petroleum-based thread getting too hot and ruining your bird.

You can also bind the bird with kitchen twine following the technique described in my Roulade post.

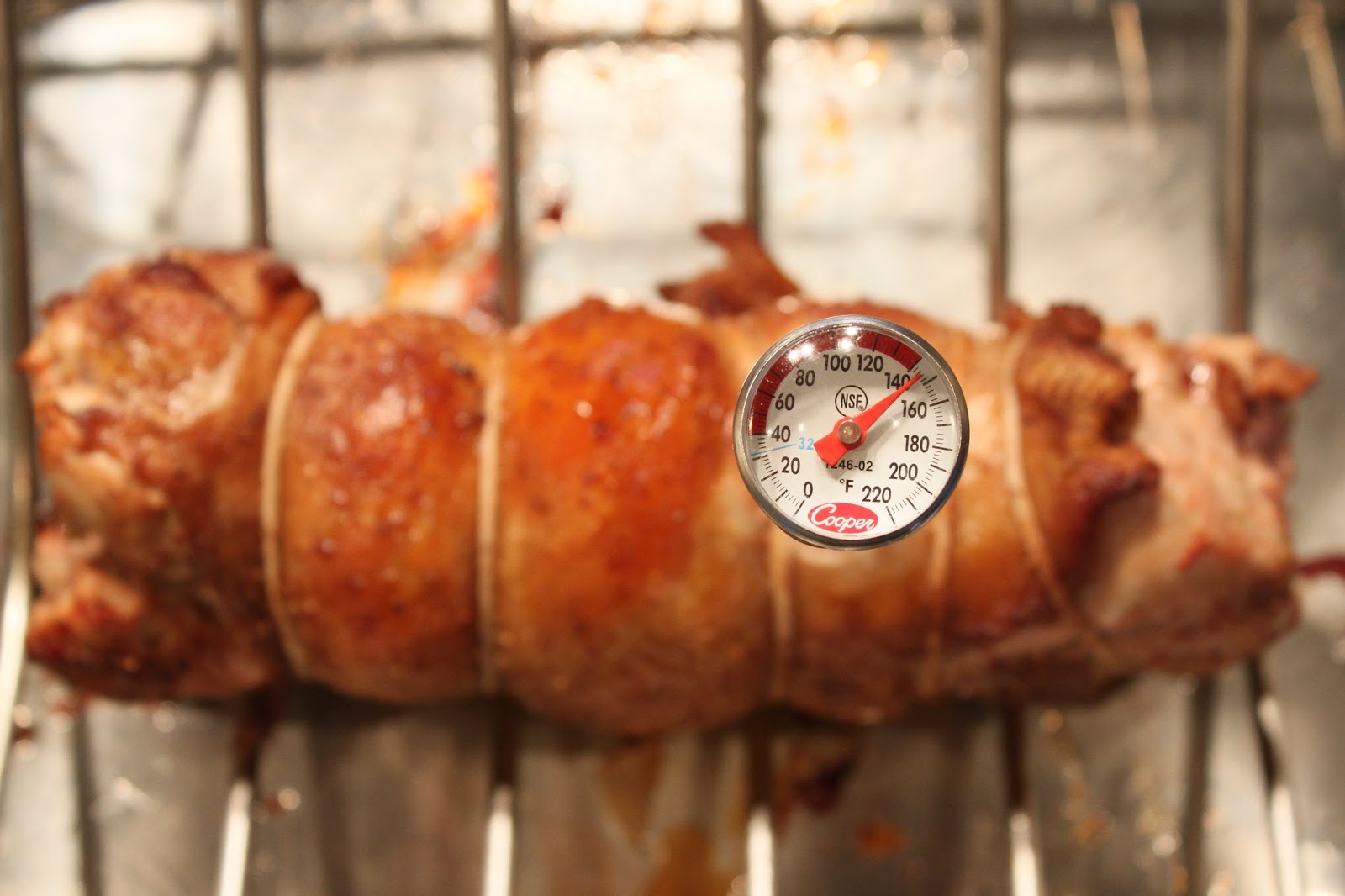

Roast at 350 until the internal temperature reaches between 155 and 160. There are those among you who will gasp and insist that this is not hot enough. Trust me, it is. The best way to protect the delicate white meat from becoming dry and stringy is to not overcook it, and will help it survive reheating the next day. After the execution of the superior deboning technique, and the advanced meat-sewing technique, do not overcook this bird. You will regret it.

While our bird was roasting away, my counterpart steamed some carrots and leeks in a sieve over the stick pot, and prepared a sauce.

In keeping with the classic, old school preparation for the bird, Gareth made an equally classic - and equally forgotten - sauce: a thickened veloute. This is basically a white sauce of butter, flour, heavy cream, and stock with an egg yolk cooked at a low enough temperature so that the egg doesn't curdle, similar to a hollandaise. The result is a smooth and rich sauce with a silky texture almost like molten cream cheese.

Our chicken came out golden and delicious with lovely parts where the wings use to be that were really just stuffing and crispy skin. The breast meat was tender and moist. The veloute was the perfect accompaniment.